Autumn Report 2025

by Eva Drukker, Elien Hoekstra, Mitra Daneshvar,

Gabi Caucal & Yaren Özogul‑Görür

In the Batumi bottleneck, you often get unique eye-level views of raptors, such as this Short-toed Eagle, with dense vegetation adding to the mysterious atmosphere.

Photo by Nikolina Bukovac.

August

August opened with the familiar anticipation of a new season — the mix of excitement, nervousness, and the quiet hope that this year would bring something unforgettable. The baseline wish is always the same: that everything goes well. But what Batumi had in store for us this year went far beyond those modest hopes.

We began with bold predictions. Since the one-million mark hadn’t been reached last year, we jokingly set a new bet: Alright then, let’s break the all-time season record! Little did we know…

On the 6th of August, the coordinators arrived to start preparing for the count. It would be the first all-woman coordinator team in the history of BRC. Volunteers and trainees trickled in, until we were nine strong, ready to launch the count on the morning of August 12. Some planned to stay full season; others would join us only for half the chapter of this story. And so many more would still arrive; over 50 volunteers from 19 countries were going to join the count. This year also marked an expansion of our flyway monitoring traineeship with OSME, as we welcomed three trainees rather than two.

The first days of the count were marked by some beautiful memories. On the first morning, we were surrounded by the calls of Green Warblers and Thrush Nightingales hiding in the shrubberies around the station. It was cloudy with even some drops of rain, while we patiently awaited the first protocol species. It took some time, but eventually the one and only crossed the transect line: a beautiful Marsh Harrier — a well-deserved and expected first place. And so, it began. Even though the first day had only 5 birds on Station 1 and 54 on Station 2, we knew to be patient. These numbers would slowly build up.

Background photo by Eva Drukker.

The second day already we were treated with what we named White Stork Day! We had barely arrived at the station when they came for us and nicely streamed in between the stations, allowing all of us to enjoy. We counted a total of 107 White Storks that day, of which one group of 80, quite enjoyable with the otherwise still low number of birds. On top of that we were treated with the first Lesser Spotted Eagle of the season!

After that excitement, migration eased again, as expected for early August. These were the tough days: relentless heat, humidity, and painfully empty skies. On the 16th of August we were finally able to break the silence with our clickers — we got to count 1600 birds in total. And mind you, five days might seem like such a short time — but for us counters those mere five days seemed like an eternity. By now we felt as if we’d known each other for ages, having gone through all the riddles and stupidest of jokes, deep conversations and bold predictions on which species we would be seeing this year.

The pace kept picking up. The next day already brought a beautiful dark morph Marsh Harrier, close to our overhead! The European Rollers made their first appearance, their bright blue colours flashing against the lush green background of the mountains. Booted Eagles would now and then collide with us on station, making us grasp our camera’s to take a good picture. Non-protocol species like Sand Martins rushed by in flocks of hundreds, while European Bee-eaters circled the station with their playful rolling calls and perched in the trees together with the Golden Orioles.

Then from the 20th on, the first streams of Montagu’s and Pallid Harriers poured in — this is where the counting gets exciting, and challenging, as you need a well-oiled machine of counters to count them all! The challenge? Finding every one of those small harriers and adjusting your tactics to match the circumstances at hand. Are they spread out and nearly impossible to locate, disappearing into the clouds (gloopsing) or fading into the bright blue sky? Or are they flying in dense flocks, ungloopsing from the clouds — right above your head? It would force everyone to get all hands on deck, divide tasks, and count and identify birds at lightning speed. We felt the taste of Batumi in the air as our fingers practiced their clicking, ready for the big numbers ahead.

But the birds deceived us. The days that followed portrayed a dramatic drop in the number of birds. This was mostly the case for Station 1, enduring mornings of one bird per hour, while most birds flew to the far far east of Station 2. With the Honey Buzzard protocol approaching on 21st of August — during which Station 1 counts all Honey Buzzards — this was unfortunate news. While the people on Station 1 were squinting their eyes, Station 2 was having a blast! Days of 3000+ birds, an epic fight between a large eagle and a Steppe Buzzard, finding the first Pallid Harrier of the season, and absolutely nailing the streams of harriers passing by. Comparing the totals so far with previous years showed that we were well ahead for this time of the season.

Then arrived August 21st, a strange day that foreshadowed much of the weather we would face this season. The clouds came quietly streaming in from over the sea, while rays of sunlight broke through the clouds from the east, making the occasional showers glitter against the vegetation. Lightning struck down over the Black Sea. We ran and hid for the thunder, then sprinted back up the hill the moment the storm allowed it. Soaked to the bone, we found solace in a very grumpy, very soggy Hoopoe, flocks of at least 15 Lesser Grey Shrikes clinging desperately to wind-whipped branches, and a Hobby harassing a Marsh Harrier. We did not expect many birds with this weather, but this is where the migrational instinct of the birds really struck. Against all odds they would battle against the wind and rain, pushing their way south.

The weather remained unpredictable. Consequently, the Honey Buzzards kept being funneled over Station 2, forcing the poor counters on Station 1 to extract every possible distant speck possible from the eastern horizon. Between scorching hot days and sudden thunderstorms, we stayed alert, knowing that strange weather can still bring the most surprising appearances of birds. A prime example: on August 22nd we had the second-earliest Imperial Eagle for BRC!

White Storks appearing from the clouds, the first of few large flocks we count each season. Photo by Eva Drukker.

What's better than an European Roller in crisp morning light? Photo by Nikolina Bukovac.

Rain in August often results in Golden Orioles and European Bee-eaters taking a quick rest in the trees around station before continouing their journey southward. Photo by Paul Buntfuß.

A classic Batumi-view, a juvenile Pallid Harrier flying against the vegetation. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

An adult Honey Buzzard battling through the harsh conditions in the Batumi bottleneck. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

During our many hours standing in the rain on station, we could more than relate to this not-so-fortunate very soggy Hoopoe. Photo by Eva Drukker.

The days that followed continued to present suboptimal conditions for raptor migration — to say the least — with heavy cloudcover, rain, and strong southern headwinds. Yet as we reached the end of August the Zugunruhe (migration restlessness) was clearly kicking in among the Honey Buzzard, because despite harsh weather conditions we counted several thousands trickling through the bottleneck on the 26th and 27th. However, they would often fool us into thinking they were going to cross the transect line! Like slugs they would approach it. We would have our fingers on the clickers, ready to click the birds that we had been following for so long from up north. They would stop, right on the transect line, perch in the trees, playing hide-and-seek behind the mountain, or disappear into the clouds. Coordination between stations became essential. We would work together well, courteously taking over each other’s streams on the moments one of us had no visibility due to the clouds.

With the cold wet days we rewarded ourselves with warm Khachapuri and coffee from the café at Station 2. And the birds rewarded us as well as the clouds would push them down through the mist, giving us unforgettable views after all our patience. With all this rain and few birds, it was probably a good idea to have more people take days off, so that they would be well rested for when the big days would come. Right? But the big day… came sooner than expected.

On August 28th the chaos began. What started as a quiet morning, turned out to be one of the most hectic days of the season. Out of nowhere, the Honey Buzzard streams came pouring in. Kettles here, kettles there, and to top it off, massive flocks of White Storks all around the station! We would be lying if we said that we didn’t feel slightly overwhelmed. We realised soon that every available hand was going to be needed. Consequently, people who were supposed to have the day off came sprinting, out of breath, up to the station to help — and thank goodness they did, because the streams just kept coming. Our clickers went wild trying to keep up with the monster kettles of Honey Buzzards, our eyes and brains put to maximum capacity to pick out the Black Kites, Booted Eagles and Marsh Harriers. Meanwhile we also needed to keep up with the many Montagu’s and Pallid Harriers moving through! We ended up with a day total of nearly 50 000 raptors for both stations combined! We caught our breaths and carried on, now mentally braced for 50K-plus days as the new normal. With a close-by immature Steppe Eagle and the first Egyptian Vulture of the season on the 29th and a day record of European Rollers (697 individuals) on the 30th, we moved very satisfied into September.

An adult Honey Buzzard decided to take a rest from the flying through bad weather by perching in a tree right in front of us! Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

Juvenile Egyptian Vulture cruising over station. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

Ready. Set. Count! Photo by Eva Drukker.

A picture that beautifully captures the magic of Batumi, with thick clouds rising from the Colchic rainforests as a male Marsh Harrier makes its way south.

Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

September

We started off September strong, with a big day and not one, but two beautiful Egyptian Vultures: a lifer and long-awaited species for one of the counters who happened to be leaving that very day. September is the period that Black Kites become more abundant, thereby mixing into the streams of Honey Buzzard — giving a new dimension to our counting skills. This is the moment when it becomes challenging for the identifying counter!

The 3rd of September was… well, an interesting day. It was not the quantity or quality of raptors, but the weather and how it affected the birds’ behaviour. It was cloudy, it was rainy and thunderstorms were raging over the Black Sea, with heavy clouds racing towards us from the south. Lightning struck, sending sparks skittering down the iron stair rails. Huddled together in the safe corner of Station 1, we waited until the raging storm would subside. We were convinced no bird would dare fly while the thunderstorms were dominating the bottleneck, but we had underestimated their determination.

Suddenly, Honey Buzzards appeared out of the clouds. We almost missed them as they were flying unexpectedly high above our heads. Here and there single harriers emerged. The wind was so strong that it forced them to move sideways like crabs, but still they went south, all the way across the transect line. It still seemed calm, but it was only the calm before the storm. Shapes started to emerge from the mist — first one, then many — until suddenly the fog lifted and the sky exploded. Streams of Honey Buzzards, mixed with Black Kites, Booted Eagles and harriers in their thousands, all rapidly crossing the transect line as if fleeing for their lives. We jumped to our feet, and counted. The rain came back, and shifted to the sun beaming down, then cold again, rain, heat, glare, hour after hour until the thunder returned and shut everything down. We packed up and made a run for it back down, unaware that one of our coordinators was still behind the station, calmly finishing an important phone call while thunder cracked and dogs barked at her. She returned to an empty station… And a kettle of over a thousand Black Kites right in front of her. She took care of them single handedly, until backup arrived. Our hero.

Background photo by Elle Heiser.

Another protocol we use in Batumi is the Harrier Protocol. A small group stays in a guesthouse near Station 2, allowing both stations to start at dawn and catch Harriers in the golden morning light. The Montagu's Harriers typically arrive with the first rays of sunshine each morning. Tracking them at all the different altitudes had us contorting our bodies and squinting upward until we cramped, but it only sharpened our teamwork. The early hours on station 2 are often blissful, perfect for studying individuals, practising ID, taking moult photos, or simply enjoying their elegant passage. But not every morning on Station 2 is peaceful. Sometimes Station 2 is quiet while Station 1 is overwhelmed, leaving us watching the spectacle in the west without being able to help. The 5th of September was one of those days.

The 5th of September we rebranded as Migration Madness Day. What started as a rather easygoing morning with some streams in our far east and harriers all around, soon turned crazy. Just before noon, a wall of Honey Buzzards mixed with Black Kites came at us from over the Caucasus mountains! We were non-stop counting for 5 hours when the birds finally let us have a break, and we were reminded that something like lunch existed. We reapplied our sunscreen, drank water, and ate our lunch while it slowly sank in what just happened… We counted over 100 000 birds! While the afternoon sun came down, we enjoyed the somewhat slower movements of Booted Eagles and large eagles. What a day. And for the whole day, Station 2 could do nothing but stare with open mouths at the seemingly never ending streams of raptors moving over Station 1. Although Honey Buzzards are perhaps the most phenologically predictable migrants in the bottleneck, their passage never ceases to amaze and remains an unmatched spectacle to witness. Viva Batumi!

September in Batumi is characterised by a high diversity of raptors, with up to 25+ species a day! This seasonal richness was reflected in the increasing numbers of large eagles, with Lesser Spotted Eagles being the most abundant. Furthermore, on September 6th, we noted the first Oriental Turtle Dove and (long-awaited) Crested Honey Buzzard of the season, as well as hundreds of Booted Eagles. Not long after we had 14 Cresteds in one day on the 11th and a group of 85 Great White Pelicans on the 13th, that squeezed into a perfectly formed circle on the sea, awkwardly drifting south. The Steppe Buzzards also started to pick up in numbers, with the first real streams arriving nicely timed after the Honey Buzzard protocol ended. With the high numbers and high diversity, we would continue counting until way after the official end of the count. The birds, it seemed, had no intention of respecting our timetable.

The non-protocol species kept us entertained too — especially on the rainy days when migration slowed to “only” 7,000 birds or so. We had a female Levant Sparrowhawk perched close to station, a group of 18 Night Herons passing by and a flock of over a 100 Ruffs on the 10th.

Halfway September. You think you have everything under control, but the birds won’t let you. The 14th of September was another day of chaos. And it was not the Steppe Buzzards being the culprit here! It was the Black Kites that must have picked up some bad behaviour from them. And they were going everywhere, kettling in our faces, from one side of the station to the other — seemingly eager to be double counted. And that while at the same time the Booted Eagle highway had opened up. The golden hues of their upperparts had become even more beautiful with the arrival of the juveniles, especially against the dark wooded backdrop of the Lesser Caucasus foothills. 864 individuals passed through on this day and got us all hyped… Were we going to break the day-record for it? Amidst the hectic search for more Booted Eagles in the endless stream of Black Kites — hoping to break the day record — we didn’t even realise we were actually breaking the Black Kite autumn day record, with over 43 790 individuals counted from Station 1 alone. The Booted record we did not break in the end, reaching 3rd place with 864 birds — but not for lack of trying! We had some very dedicated counters’ eyes locked on the otherwise very quiet west, looking for sneaky Booteds crossing by.

But then we realised we were already tantalisingly close to reaching the one-million-raptor total for the season. On 15 September, after just experiencing a relatively big day of around 22,000 birds, we found ourselves ‘only’ 43,000 birds away from the milestone. We weren’t even halfway through the season yet — hitting a million now would be the earliest in BRC history! So of course we started taking bets on the exact time we’d reach it that day. A few cautious souls predicted the 16th. Could we have been more wrong?

What is a classic Batumi sunrise? Not a cocktail, but a backlit juvenile Montagu’s Harrier passing east of Station 1 in the early morning.

Photo by Nikolina Bukovac.

The following two days passed with modest numbers, and that’s putting it mildly. Migration ceased and the avalanche of birds expected and needed was nowhere to be found. Thankfully there were at least some non-protocol species such as Hobbies and a handful of Red-footed Falcons that kept us entertained. Only one person had predicted the 17th (conveniently also his birthday) to be the day, which happened to be the exact midpoint of the season — as well as the day many counters were leaving and new ones were arriving. All of us desperately hoped they’d get to witness the million before heading home. The suspense lasted right until the very final hours. By late afternoon we had given up hope. But then, around 16:00, out of nowhere the streams decided to pick up. Clickers snapped back to life. Numbers climbed. And just a few minutes before the official count, we reached it.

ONE MILLION RAPTORS.

We reached this milestone halfway through the 2025 Batumi Raptor Count, which turned out to be ten days earlier compared to any other season. We clapped, we hugged, we cheered and perhaps shed some tears. Then we said goodbye to our half-season counters and welcomed the new counters into the excitement.

Arriving in Batumi at the start of peak migration can be a bit overwhelming, especially if it's your first time joining the count team. While our new counters were learning the station basics to communicate and count the streams efficiently in their first couple of days, they have yet to realise the madness they had fallen into! But watching their progress and your own, is genuinely marvellous. From their first days of confusion with the landmarks and clicking streams, to the confidence of taking species, ageing, and even guiding new volunteers; all thanks to the experienced long-term volunteers’ eagerness to share their expertise.

A bit of friendly rivalry between stations about rare species is always fun, but even better is when both stations witness the same spectacle. Thanks to our pilot count in Kvirike, we got to enjoy more of these shared highlights. On the 17th of September we received a message that two Griffon Vultures were heading our way. Everyone held their breath — and then there they were. It was amazing to monitor the speed at which these birds move from one station to another: they covered a distance of ~9.5 km with a speed of 28.5 km/h!

From that moment, every message from Kvirike came with excitement. It happened several times later in the season: an adult Imperial Eagle was on its way to Station 2, or flocks of Cranes. This way, our pilot count in Kvirike added a new dimension to our understanding of migration. Stay tuned for our full Kvirike report!

The weather remained stormy for the following days, from the 17th onwards. Although not much active migration was happening during these days, we still enjoyed! For example, we watched a Pallid Harrier perched closeby in a tree, followed Lesser Spotted Eagles for elongated periods of time and enjoyed the crisp looks of juvenile, chocolate coloured Honey Buzzards close to station as they were pushed down by the clouds. In addition, we had time to be on the look out for some non-protocol species, such as Wood Sandpipers, Ruffs and Hobbies (588 individuals in a single day on the 20th!). We would be surrounded by thousands of martins and swallows flickering their white bellies in the light that would occasionally break through the clouds. They would be chased by Levant and Eurasian Sparrowhawks, and Common and Lesser Kestrels.

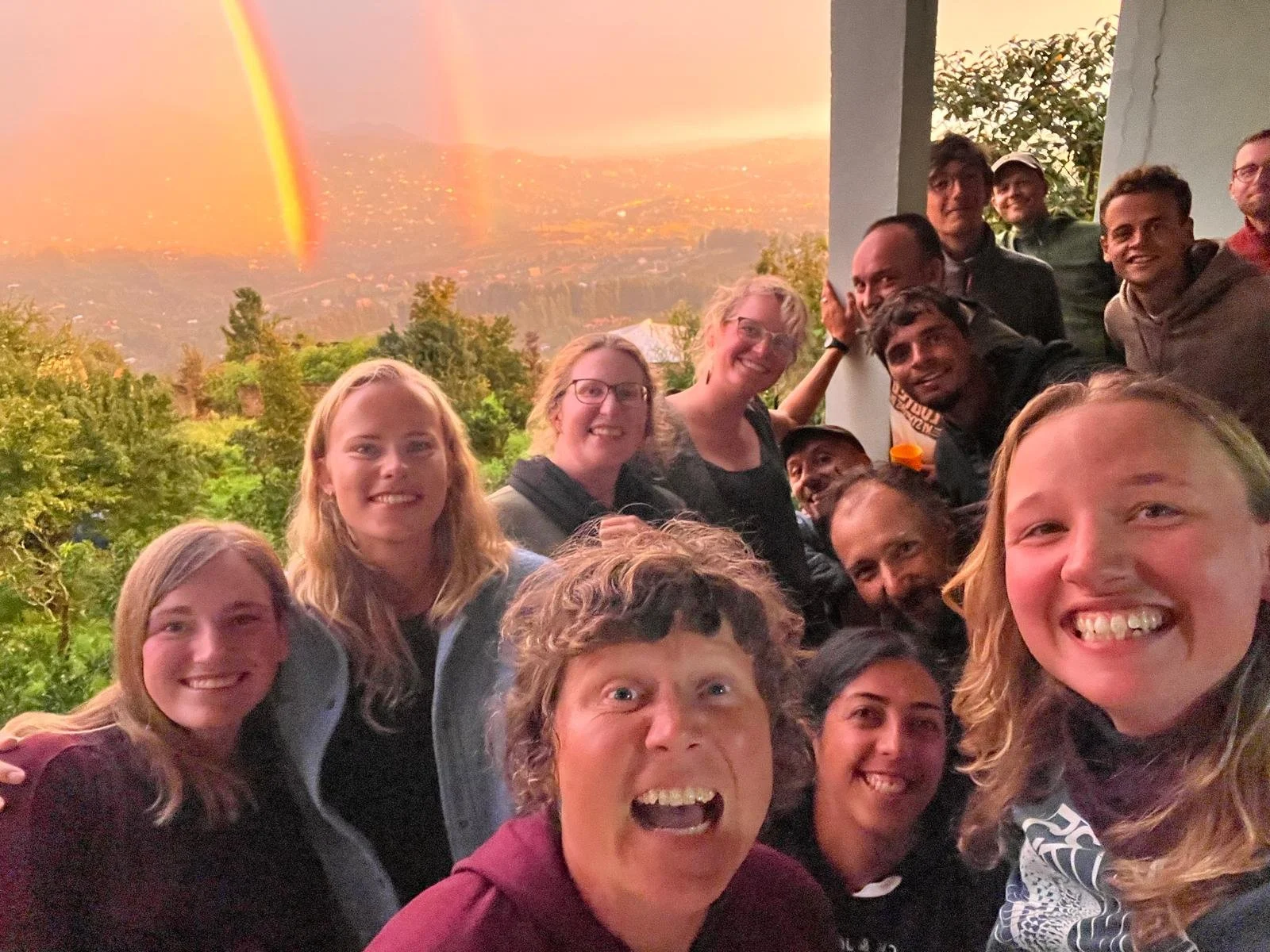

Happy faces on Station 1 after reaching the earliest one million raptors in BRC history.

During the Honey Buzzard peak, we often get close-up views of this beautiful species. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

Whereas Booted Eagles are common throughout their range, populations migrating through the Batumi bottleneck are known to contain exceptionally high proportions of dark morphs. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

For those wondering what we are looking at here... A flock of Great White Pelicans 'floating' over our transect line — pushing the boundaries of the term 'migratory soaring birds'. Photo by Sander Bruylants.

An adult female Levant Sparrowhawk taking a rest near statation1. Photo by Jonathan Meire.

A crisp juvenile Lesser Spotted Eagle showing off. Photo by Sander Bruylants.

An image perfectly capturing the magic of raptor migration at Batumi: with large streams of Black Kites moving through the heavily clouded foothills of the Lesser Caucasus.

Photo by Bart Hoekstra.

The sunny days finally returned on the 22nd of September. And with that also came challenges. Streams would shift constantly between stations, demanding for constant communication. A high diversity of birds, streams of large eagles, consisting of kettles of Steppe Eagles and Lesser Spotted Eagles in all their plumages. But some days the birds would behave nicely. They would cordially pass by, showing off different plumages allowing us to put our ID skills to practice. We were getting ready to pick out the soon-to-come adult plumages of Greater Spotted and Imperial Eagles.

And still, we were waiting for the real take-off of the Steppe Buzzards. Their migration is loved as it is feared. They will create chaos, we know, but also a spectacle. With a mixture of fear and excited anticipation we waited. And then came the 25th. The morning began in an eerie hush — no birds in sight, the sky strangely empty… The station felt like the early days of the season again, finally giving us time to talk about the important things in life. But what started as a quiet day, soon turned into one of the most thrilling we’ve had so far. Before the afternoon even began, the skies burst to life. The Steppe Buzzards were coming. And when Steppe Buzzards decide to move, they really move — sweeping across the sky in every direction, darting to the very edges of our vision, trying their best to escape our sight. But we didn’t let them. We followed them as they poured from one kettle to the next, shifting from west to overhead to east.

The spectacle didn’t stop there. The streams were filled either with the frantic swirls of Steppe Buzzards or with the steadily gliding large eagles. And then came the spectacle of the day. A Griffon Vulture appeared right in front of Station 2. Perhaps it caught the scent of our half season built up stench, perhaps it was just a young curious bird. But because it came so close it might as well have perched with us. You could see every detail of its crisp juvenile plumage, you could see its body feathers dancing in the wind.. It was all topped off at the end of the day with a juvenile Imperial Eagle trying to find its place in between the Steppe Buzzards.

Then there was this spectacular moment when a naive young Short-toed Eagle appeared out of the mist right in front of us, only to realise last minute our presence and deciding abruptly to back off with a sharp and swift move to head the other way. We had an interesting observation of a GPS-tagged Lesser Spotted Eagle at Station 1, and as we speak, we’re still trying to figure out where it came from. The second-half season migrants clearly started to dominate, with over 500 large eagles in one day. A good diversity of birds. The number of Long-legged Buzzards was also starting to stand out. Were there more this year or were we just amazingly good at recognizing them?

We finished off September with the third autumn record of Black-winged Kite for BRC, and several enjoyable non-protocol species such as a Nightjar perched behind Station 1, a Caucasian Viper on Station 2, and many Red-footed Falcons flying past our stations.

Scanning, scanning, scanning… and when you think you’ve scanned enough, maybe scan the skies a bit more. Trust us, it’s worth it!

Photo by Bertrand Vanderschueren.

Kettle of Steppe Buzzards slowly soaring up in the east of Station 2. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

Whether it was the stench of our counters after standing on top of a hill for over 1.5 months, or simply a Griffon Vulture wanting to be photographed, in any case an unforgettable close encounter with this truly majestic species. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

Speaking of close encounters, not much more intense then the piercing eyes of a Short-toed Eagle. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

We counted over 400 Long-legged Buzzards this season, providing great opportunities to study their variable plumages. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

Black-winged Kites are a rapidly expanding species across their range, and the Caucasus is no exception. Yet this is only the third autumn record for the BRC. Photo by Nikolina Bukovac.

Every season, we have the chance to observe the local, endemic Caucasian Vipers around our stations. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

Kvirike

Every year, the same questions occasionally pop up at the watch sites: What would we see if we counted from higher up in the foothills of the Lesser Caucasus? Would we see more harriers? Are birds flying above the clouds? Would the eagles fly closer?

This year, thanks to a generous collaboration with Chalet Kvirike, we finally had the chance to find out through our pilot counts at Station 3, ‘Kvirike’. Located just 10 kilometers northeast of our Shuamta watchpoint and 600 meters higher, we monitored raptor migration from August 21st to October 21st, in parallel with our ongoing counts at Sakhalvasho and Shuamta. Rest assured, birds counted from Station 3 were not included in the total 2025 season counts.

The number of raptors was lower, with 234,898 raptors recorded in total, mostly because the vast majority migrated too close to the coast — almost ten kilometers from Kvirike — to be properly counted and identified. However, the quality of raptor migration we witnessed exceeded all expectations. Honey Buzzards and Montagu’s Harriers often flew at eye level, providing fantastic views and photo opportunities. Due to the high altitude of Chalet Kvirike, our team frequently disappeared into a blanket of clouds, which occasionally turned into magical moments when we reappeared above the clouds, in the sun, with kettles and streams of raptors moving south, seemingly unbothered by the thick cloud layers. These moments were absolutely unforgettable and unlike anything we had experienced at our other count sites.

Beyond experimenting with monitoring from different sites, we were particularly interested in the Kvirike area. While it has been known as a hotspot for illegal raptor hunting, Kvirike also stands out for its remarkably pristine natural forests and strong potential for ecotourism. Similar to our experiences in Sakhalvasho and Shuamta, where raptor hunting was once far more prevalent than it is today, we aim to support a positive transition in Kvirike through our continued presence, monitoring efforts, and recommendations for sustainable ecotourism development. Encouragingly, after just one season of monitoring and awareness-raising with local authorities, promising plans are already underway to move the area towards becoming a hunting-free zone.

We hope to continue this collaboration in the coming years and strengthen protection and enforcement in the area and wider region, continuing to make the Batumi bottleneck a safer place for the more than one million raptors migrating through it every autumn. Make sure to keep an eye on our website and newsletter for updates and future plans on the Kvirike project.

Background photo by Erik Jansen.

One of the thousands of Honey Buzzards that flew by at eye-level and within meters distance of our watch site at Kvirike. Photo by Guus van den Berg.

At the fringes of the Colchic rainforest, Kvirike is surrounded by ancient trees hosting a variety of local species, including this Tawny Owl that accompanied us all season. Photo by Richard van Vugt.

Because of the mixed old forests around Kvirike, the area is rich with multiple scarce woodland bird species, such as this Grey-headed Woodpecker. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

This Saker Falcon is a globally threatened species and highlights the importance of protecting the Kvirike area and the Batumi bottleneck in general. Photo by Guus van den Berg.

October

October in Batumi goes hand in hand with clear autumn light, and Steppe Buzzards soaring above the green hills of Mtirala National Park, and large eagles in all their variational plumages. Meanwhile the sound of our clickers is complemented by the calls of Mistle Thrushes, Bramblings, and Siskins. Additionally, we get to enjoy the local subspecies of Jays: with their black crown standing out. The whole atmosphere on the station slowly shifts with temperatures decreasing and shorter light days, leaving us with enough time to play some football after the count, or just get together for drinks and crisps. We welcome the new counters, we play guitar and reminisce about the early days — which seemed like another lifetime.

This year, October didn’t start quietly. After some rainy days, the 1st of October became one to remember. We wisely decided to have lunch early, because we had a feeling for what was coming, and we were right.

Background photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

After a rather quiet morning, the chaos started a bit after 10:00. It was the feared, but highly anticipated Steppe Buzzard peak day. Streams of Steppe Buzzards stretched wide across the sky — massive flows covering nearly four kilometers, like a blanket over both stations. Dividing that between two stations was a challenge, demanding sharp communication both on and between stations. But we nailed it, with the counters communicating in sync.

In just 10–20 minutes, more than 14,000 birds passed through. Within the chaos of Steppe Buzzards, we tried to pull out the other species — especially the large eagles gliding slowly and elegantly among them. Extracting them from the mass and identifying as many as possible was the real task, and even in the whirlwind, we enjoyed unforgettable views: juvenile Imperial Eagles, Steppe Eagles, and beautifully marked Greater Spotted Eagles. The morning light made aging easy, but by afternoon the sky was so packed and the backlight so harsh, that many had to be counted simply as large eagles. We did what we could.

By day’s end, the group photo captured everything: exhausted faces, smiles stretching from ear to ear, hugs and high-fives as we managed to count 170 000 birds that day! What a massive day it was, truly extraordinary and unimaginable to see such large numbers of raptors. Hundreds of Short-toed Eagles, Lesser Spotted Eagles and large eagles combined with thousands of Steppe Buzzards. Dazzled, we walked down in silence, still processing the day. Down at the guest houses the brightest double rainbow we’d ever seen appeared, as if to congratulate us with the successful day. Could October get any better?

So! Onto the second day of October. Not a moment of rest, as also this was an important day. It was the day that we broke the all-time season record of Black Kites for one season! Midafternoon we reached a staggering number of over 350 000 individuals. A great tribute to our sponsors Kite Optics, that funded our research by donating optics.

Besides the Black Kite record, we topped this day off with a Cinereous Vulture and a Griffon Vulture!

The third of October was also worth mentioning. An intense day in the sense of insects: they dropped down on the tarp like raindrops from the sky. This made for some spectacular observations where we observed — for the first time in autumn — Black Kites catching insects mid-air and eating them on the wing! So far, we only noted this behaviour during our pilot spring counts in 2019, 2020, and 2022, which we described in this publication.

Throughout October we often see large flocks of Jays moving bush-to-bush past our stations, note the typical head pattern of the local subspecies (ssp. krynicki). Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

A lonely Steppe Buzzard flying against a backdrop of dark rainclouds moving into the bottleneck. Photo by Richard van Vugt.

One of the giants: an immature Steppe Eagle. Photo by Tom Bovens.

Not many birds or plumages are prettier than a juvenile Greater Spotted Eagle. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

Exhausted but happy faces after a day with 170.000 raptors counted!

A juvenile Honey Buzzard departing after a quick rest in one of the dead trees around Station 2. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.

We would like to take this opportunity to thank Kite Optics for once again providing us with (stabilised) optical equipment and for sponsoring our annual T-shirts. Access to binoculars or scopes can be a barrier for some of our volunteers and trainees, but thanks to Kite Optics, everyone was able to fully participate in the count this year using state-of-the-art equipment.

And yes, thanks to Kite Optic’s stabilised binoculars like this APC 14x50, your binocular view never becomes shaky — perfect if you have to count more than 1.5 million raptors!

10% Discount on Kite Optics

We can offer a 10% discount on Kite Optics ordered through their webshop when using discount code BRC2500KT. You can fill in the discount code while checking out.

October brought us many interesting days. It brought us the days with Stinky Bugs and ants flying in our faces, sticking against our sunscreen covered sweaty skin. A day with a group of 43 Jays that flew around the station and 33 Ravens passing by. It brought us the Eurobirdwatch days and the Global Big Day — the latter with a casual two thousand swallows and 18 Red-breasted Flycatchers. It brought us the day of the putative Red Kite on the 4th. It continued with the big eagle days, arriving in high diversity and plumages. We had 866 Lesser Spotted Eagles and 904 large eagles on the 3rd and 105 Greater Spotted Eagles, 36 Steppe Eagles and 7 Imperial Eagles on the 7th. At this point in the season, the bright plumages of the juveniles would give way to the black rectangles of the subadult and adult birds. This is the best period of the season to practice our identification skills for these magnificent but challenging species group! Each Imperial Eagle gave enthusiastic shouts amongst the team. And for playing The Imperial March over the walkie talkie — as per tradition. The juvenile Greater Spotted Eagle slowly became most people’s favourite, with its crisp silvery remiges and bright white lines across the flight feathers.

Whereas we felt this season had already surpassed all of our expectations, the raptors weren’t done with us yet. On the 5th of October, we were anticipating breaking the all-time season record of total raptors counted, but the birds came trickling in one by one that day, agonizingly slow. And while we were nearing the end of the day, we were finally able to start the countdown:. 20.. 19… 18…

3… 2… where was that last bird? The stream had ended. It stayed awkwardly quiet for a few seconds… But then, through the mist came the 1 422 172nd bird! A juvenile Black Kite; iconic for this season, with its beautiful crisp golden speckles contrasting with the rest of its dark plumage. We did it. What a season. Meanwhile, we still had little over two weeks to go. Could it get any better?

Lesser Spotted Eagles, such as this adult, are among the more entertaining bulk species in October. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

Amid the hundreds of eagles, the few Imperial Eagles always provide plenty of excitement among our counters. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

We proudly present the record-breaking 1,422,172nd bird of the season: a juvenile Black Kite flying through the fog east of Station 1. Photo by Bart Hoekstra.

A typical October view: a juvenile Steppe Eagle moving south east of Station 1 against the ridge, beautifully showing the key identification features.

Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

The count continued and while daily totals slowly decreased, records kept being broken. On the 6th of October we broke the season record of Black Storks. In addition, on October 17th, we secured the season record of Long-legged Buzzards, although note that we only started monitoring this species in 2019, and the day record of Stock Doves (350 and 580 on station 1 and 2, respectively). Among the many Long-legged Buzzards we counted this season, were also several dark morphs, an absolutely stunning and surprisingly scarce plumage to see!

Slowly but surely we neared the end of the season. The days became slower and more rain forced us to come with alternative entertainment programmes. Rock throwing, dancing, telling each other riddles, playing bird-guessing games, running up and down from the shelter to the station due to many single showers, coming up with the most genius memes, watching a worm crossing the station in one and a half hours. Nevertheless, we had nothing to complain about. We were exhausted, but new counters brought new energy and the pearls kept showing up. Imperial Eagles entertained us, along with the beautiful plumages of Steppe Eagles, and exciting moments of fulvescens plumages of Greater Spotted Eagles.

The days became slow. Very slow. Was migration finished? Did we just peak early this season? On the 12th Station 1 had only 5 birds! Luckily we were compensated with a Yellow-browed Warbler next to station!

Though, we had nothing to fear. After the rain, the birds migrate again! From the 14th onwards, migration picked up. Over 6000 birds on good days, along with Griffon Vultures, Stock Doves and Cranes. And then, we got a day of 19 000 birds out of nowhere, giving us a push for something very exciting. Could we perhaps reach… 1.5 million birds?! All of a sudden this number seemed to be within our reach. We had exactly one week left before the end of the count. This was going to be tight.

The 18th of October was going to be the day that the three coordinators would go to Kvirike (Station 3) and leave the other stations in the hands of their trusty long-term counters to coordinate. That day, we all eagerly watched from our respective stations as the birds slowly passed by, until finally the 1.5-millionth bird — a perfectly fitting Steppe Buzzard — crossed the transect line.

One. And a half. Million. Raptors. What a number to be reached!

It was a day to remember, a true milestone after 17 years of counting, highlighting the importance of the Batumi Bottleneck. It demonstrated once again why our work of monitoring and conserving here is so important. We celebrated vigorously of course, like we do in Batumi, with Cha Cha, Georgian wine, relatively cold beer and good music. We danced with each other until midnight and went to bed — rosy, happy and content.

The final three days wrapped everything up nicely. They were slow, gentle days, preparing us mentally for the end of the count. The Wood Pigeons finally started flying and a full day of rain gave us a welcoming pause before the very last day of the count on the 21st of October. We had our last dinner with everybody who was still present and enjoyed some last dancing and a starry starry night.

Hen Harriers are a typical October species. This juvenile seems to cast a few judgy looks, perhaps unimpressed by being photographed. Photo by Tohar Tal.

Flocks of Black Storks often fly between stations, posing the ongoing challenge of photographing them together with the respective station. Photo by Richard van Vugt.

Nevertheless, it remains most enjoyable to observe Black Storks at close range. Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

At the end of the season, our counters are often treated to flocks of Wood Pigeons. Although enjoyable, they remain a challenge to count! Photo by Richard van Vugt.

It's not often that Stock Doves come this close! Photo by Marc Heetkamp.

Group picture after our final, well-deserved dinner, with many toasts to an unforgettable season.

Batumi is a unique place in so many ways. We all come thinking that you are there for the birds. But in the end what draws you in and has you return year after year are the people. You find yourself on top of a hill with others who share the same peculiar passion — people willing to stare at the sky for hours on end, day after day. And you learn from everyone. Not only how to count birds, but everything around it: how to count birds with a hangover, how to push yourself through scorching heat, thunderstorms, exhaustion, and whatever else the season throws at you. You leave feeling fulfilled, proud, and carrying a quiet kind of happiness that stays with you long after you’ve gone home.

It was a wonderful season with all the birds one could wish for. The group was extraordinary and gave everything they had in them. We want to thank them so much for that. We got to enjoy the most delicious Georgian meals and experience the kindness and generosity of the Georgian families. Our thanks go out to Kite Optics for sponsoring us and OSME for supporting our Flyway Monitoring Traineeship. We also want to thank the host-families for the wonderful care they take of us. Without them we are nothing! And last but certainly not least, the many generous people whose donations made this count happen!

See you in 2026!

Background photo by Motahareh Hakiminejad.

Continue reading below for more from this autumn count

World-class migration monitoring soars or falls with your support!

We are raising €30,000 for the 2026 edition of the Batumi Raptor Count. Help us reach this goal with a one-time or recurring donation.

Background photo by Marc Heetkamp.

More from this year’s Autumn Count

What to do during a day-off at BRC?

Each counter gets one day off per week, the perfect occasion to catch up on sleep, do some laundry, or make an Instagram post… or, who are we trying to fool here, go birding! The Batumi area is a major bottleneck not only for raptors but also for many other migratory bird species, and it hosts a wide variety of local residents as well, making for excellent birdwatching opportunities.

Most popular, of course, is the Chorokhi Delta, famed as an important stopover site for migratory birds such as waders, ducks, and songbirds, and known for its exceptional track record of scarce species and true vagrants. This reputation was once again confirmed this year, with counters finding Oriental Skylark, Asian Desert Warbler, and Blue-cheeked Bee-eater. The discovery of what is assumed to be only the second Three-banded Plover record for Georgia, found by an ecotourist in October, put smiles on many faces, especially among those who missed the first record two years ago.

On days when rain was too heavy for a stroll through the Delta, there was always the option to go seawatching or birding along the Boulevard. Seawatching sessions provided enjoyable views of dozens of Arctic Skuas, hundreds of Little Gulls, and several Nightjars coming in to land while being harassed by Hobbies and Peregrines. The Boulevard, a chain of artificial parks stretching several kilometers along the Batumi coastline, offers an ideal refuge for migratory songbirds during storms. Although these areas may have limited ecological value as stopover sites, they do provide excellent urban birding opportunities! With bushes full of Common Redstarts, Robins, Sylvia-warblers, and Chiffchaffs, a rarity is always possible. This year, for example, a Pine Bunting was found.

After the count had ended, many people stayed for a few more days to enjoy each other’s company and explore the region further. As a result, one group climbed the deciduous mountains of Mtirala National Park, an area designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site several years ago, while others explored the Poti area. For birdwatchers, Poti usually includes the muddy shores of Maltakva Beach, an excellent site for waders and gulls, and this year also for a remarkably fearless, or featherless, Arctic Skua. Nearby Paliastomi Lake offered views of one of the few resident pairs of White-tailed Eagles in the country, a Great Bittern flying over the reedbeds, and, most memorably, a Eurasian Otter jumping out of the water.

Background photo by Filiep T’jollyn.

Three-banded Plover. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

Short-eared Owl. Photo by Tohar Tal

Little Gull. By Eduardo Campos Wals

Wryneck. Photo by Jonathan Meire.

Asian Desert Warbler. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

Menetries Warbler. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

European Nightjar. Photo by Tohar Tal.

Northern Wheatear. Photo by Matthew Sprangers.

Pine Bunting. Photo by Tohar Tal.

Long-eared Owl. Tohar Tal.

Brambling. Photo by Filiep T'jollyn.

Arctic Skua. Photo by Eduardo Campos Wals.